By Millicent Borges Accardi

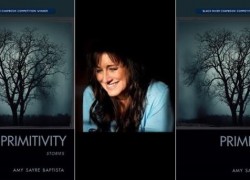

With heritage in Madeira, the writer Amy Sayre Baptista’s work has appeared in The Best Small Fictions (2017), Ninth Letter, The Butter, Alaska Quarterly Review, and other journals. Her flash fiction chapbook “Primitivity,” winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition, spring 2017 is forthcoming from Black Lawrence Press this fall. She has been SAFTA fellow (for a residency in Tennessee), a CantoMundo fellow, and was a scholarship recipient to the Disquiet Literary Festival in Lisbon, Portugal. She performs with Kale Soup for the Soul (a Portuguese-American artist’s collective), Poetry While You Wait (a Chicago-based writing group) and is a co-founder of Plates & Poetry (a community arts program focused on food and writing). Baptista has given readings at the Poetry Foundation, Brown University and UMass Dartmouth. She holds an MFA in fiction from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and teaches humanities at Western Governors University. She lives and writes in the state of Illinois.

In this interview for the Portuguese American Journal Amy Sayre Baptista speaks of her creative process and the publication of her first book where she finds her own voice and brings many other voices out.

Q: Primitivity is your first book? Congratulations! How long did it take to complete?

A: Yes, this is my first book. I wrote the pieces over a couple of years and published most of them individually, and they started to take shape as a manuscript.

Black Lawrence was the 2nd contest that I submitted to. The first responded with a very complimentary note on the voices [in the book], but said they didn’t understand what I was trying to do, and asked me to reconsider the arrangement and placement of the stories before re-submitting, so that everything worked together more palpably.

Q: What did you do when you found out you had won the Black Lawrence chapbook prize?

A: Maybe a brief and heartfelt scream-cry. Jumped around. Called at least one person and spoke incoherently.

Q: Your manuscript was chosen out of 700 entries. Who was the judge?

A: There was a panel of judges who were Black Lawrence Press editors as I understand it. I don’t remember everything, but they commented on the images and character driven nature of the stories. Recently, I did a reading and Simone Muench introduced me. She is a Black Lawrence editor, though I don’t think she was on the panel that selected me. Anyway, she gave me the most amazing introduction and compared my work to Flannery O’Connor and The Night of the Hunter by Davis Grubb.

Say my name next to Flannery O’Connor and mean it, listen, it does not get better than that. However, I had never read or heard of this book by Grubb and it’s brilliant. So, that meant a great deal. Particularly because Simone’s book Orange Crush is one I have read and reread. Truth is, as you well know, this business is mostly people telling you no, not quite, or flat out forget it, so when you have someone sincerely speak to your work, I think we are allowed to savor it for those rainy rejection letter days.

Q: Did you submit the work to other places?

A: So many amazing journals published the stories as single pieces, The Butter (The Toast), and Ninth Letter did an audio version of the séance pieces. Corium, Smoke Long Quarterly, Sundress, so many great hard-working journals that it was an honor to be in. I was thinking, ok, if these work as singles, surely they work together.

Q: What literary influences did you have?

A: I still remember reading, Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters, reading it in Mr. Mahlandt’s freshman English class, and it was the first time I really linked poetry and first person point of view, that storytelling and poetry is a coisa! It’s a thing! It was a revolution!

So, I started writing little snippets, or stories that came to me from images. For example, a boot floating in a river, a gate hanging open like a jaw in a pasture at twilight. Edgar Lee wrote as if voicing a tombstone, and I thought that’s what happens to me. I picture something and that “something” starts talking in my head. I asked so many questions about that book [Spoon River] in class, and I remember even some of my friends were like, “Seriously, shut up.”

But, I had found an origin text for my voice. I don’t know what other people call the texts that they are in conversation with but for me those are my origin texts. Those books and stories that just by reading them gave me permission, encouragement, and a way forward. The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros, my mother reading Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” to me as a bedtime story, “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson, and later Pessoa.

But especially those scary tense stories, those said to me you can survive where you are and what you are going through if you have the language for it. When I was in high school, a lot of local farmers and ranchers were going bankrupt. It was a terrible time in rural communities. We knew families who lost their homes, their livestock, or a parent committed suicide due to the stress and finances. It was an ugly time. And, I started writing these little (what I call) novelinhas (was my secret name, majic things NEED a secret name, ok?) – tiny novels that were voices connected between the dead and the living. I just found some of [my journals] while cleaning out a closet at my mother’s. In a little blue suitcase I used to carry around (yes, I was a weird kid). I had a book for spells and cures. For instance, in my little handwriting, I had written, “Me and daddy cut the warts off a steer’s neck. Fed them to him in the corn. Daddy says it works, not sure about for people.”

My sister nearly fell dead laughing when she read that. This little yellow notebook is full of similar wisdoms.

Primitivity by Amy Sayre Baptista available at Amazon.com

Q: What were the stories you first created from the voices you heard?

A: One was about a girl who died of a fever in my parents’ house when it was a stagecoach stop, and another was about a farmer who shot himself because the insurance money would get his family out of debt. Then I combined the two in a linked narrative where she walked with him to the creek where he pulled trigger.

I remember that my teacher, Mr. Mahlandt, asked me about why I would think to write about suicide, and we had a conversation about looking and listening as a writer, and I told him I heard voices talking in my head. He let me know that was ok and that was just my creativity talking. He was everything the best teacher should be. It meant a lot to be heard by someone I respected.

The sad thing is, he killed himself about six years later when I was at university. I always think how profoundly he helped me become a writer, and how I thought his life was perfect. That he was perfect, and in my heart he is. I never got to say thank you, so I rewrote a version of that story to include in a longer manuscript.

Q: What is the importance of trauma?

A: To my work, the importance has been the ability to unwind fear and despair with language, to move it out side of me so that it does not consume me. Trauma has long arms. It keeps reaching you through years, generations even. As a survivor a sexual assault, there are days that the past is too much to carry. Writing has been (and therapy) a way to shape the darkness that comes with traumatic memory. Many of us have trauma in our childhoods whether it is physical, emotional, or financial or all the above. My body processed trauma through these little stories that started talking [as if] from the bones of dead cattle, overgrown graves and open gates.

There are so many tiny 3-5 plot cemeteries along roadsides or in pastures or fields in the places where I grew up; it never occurred to me that the dead were not [right] there with us. Where else would they be? I mean, who says the next place is far away? It might just be shed skin, brighter, shinier, all the heat and none of the humidity.

Q: What is the goal for your book?

A: To tell really good stories that people want to tear though, and, then, late at night and two days later are still thinking about them, the stories or an image is still working on them.

I feel like the best stories I ever read did that to me. I hope mine do too. People tell me I write scary tales, but I really just set out to write with emotionally honesty. Perhaps fear is a side effect of truth? Wouldn’t that be something! I love to write tension, and feel of tension in a narrative. I always strive for a kind of tautness and look for various ways to achieve and break tension, including humor. I believe, and this goes back to my little novelinhas and trauma, that silence is a grave. I want to break the graves open and bring the voices out.

Q: The book comes out this fall, do you have a Launch Party planned?

A: We do. I am working on a one woman show that I plan to launch in early 2019, maybe January. That will serve as the book launch. We will do it as a Plates & Poetry event tying a menu to the book.

Q: What about a story’s location? The importance of place?

A: I wanted to look at a rural and river community and [how] it sits between worlds, natural and supernatural, along with the diversity of characters who inhabit that space who are rarely heard.

I can say it better. I really wanted to unpack the grotesque: terrible, wonderful, funny, violent, empathic, all these polarities that exist in rural and river towns and communities. I think the nexus was that house where I grew up was a stagecoach stop called, The Halfway House. So many people passed through there in written history and in apocryphal stories that it was waiting to be written.

Q: You have a background in Portuguese-Appalachian or Portulatchian. How do the two cultures merge? Where do they merge?

A: My mama says that when she started dating my father one of his old aunts went to his mother and said basically, this girl’s people are Portuguese and divorced! Either one should have been a stopper, but the two together was an intended atom bomb. But, it came round because here I am writing this world that they were not supposed to be together in. My mother’s family came from Santo da Serra, Madeira, it’s a village in the mountains. The mountains and forests there are bewitching, and to me there is a likeness in custom to Eastern Kentucky and Tennessee. Not to over simplify but, in the end, they had more in common than they had differences.

Q: How important is juxtaposition, the push and the pull between two cultures?

A: I remember seeing this play a few years ago in Brooklyn, called Red Velvet written by Lolita Chakrabarti, and I was so moved by the portrayal of a character struggling again his own art and the racial dislocation inherent in performance as prescribed by the theatrical canon at the time. I bought the manuscript afterwards, and I was so broke. It was book or meal and I chose the book. I guess you get fed where you need it. There is a line where the character says, “something about velvet–a deep promise what’s to come, the sweat of others embedded in the pile. As crushed map of who was here folded in.” That’s Portulachian – the deep crush, a map remade of unwanted people who met and made it together against those who would tell us we do not exist, that even our memory of us is not real.

Q: How did Red Velvet affect your work?

A: Now, this play has no literal connection to where I am from, but– at the same time–it has everything to do with it. All the ways we get dislocated based on race, gender, ethnicity, and ways patriarchy builds our reality, and how we spend our lives sorting the construction we are built into.

Q: What’s the play about?

A: It’s a history of Ira Aldridge, an African American actor who basically left the US to perform in Europe because of gross restrictions on his acting and grave threats. But even London never gives him his due. The play is phenomenal. Clearly his experience is not directly mine, yet it extended a light into my own processing and understanding of how my community was built and unbuilt by us and by others. The play pushes back hard on the idea that Shakespeare is for everyone, and Aldridges life is that lens.

Being of Madeiran descent in the States is like that, the Portuguese experience is already defined by East Coast communities and their scholars. You will be told that Portuguese people come from the East and West Coast. You might get an aside about the few who struggled into the mid-west or mid-south, but ”they have all disappeared now.” I am the descendant of those supposed “disappeared.” There is not one defined Portuguese-American experience, and to suggest such is to reduce us all.

Q: Ancestors from the islands?

A: My people, Madeirans in the Midwest and midsouth, have no history according these scholars, or if they do, it is one that was written by no one that knew us. They missed that fact that the wicker making in Santo da Serra was carried on in Jacksonville, Illinois. They missed so much because to see it would mean to let go of their own notions.

Primitivity has its own DNA. The canon would tell me that my people are no one and from nowhere, so I located my allies from everywhere, particularly in the broader context of Latinidad. Why would you tell a beating heart it does not exist?

Q: With such a disparity of differences, which draws both communities together?

A: The mountains, the water. The folclorico. The bruxaria. I have a series of poems about river witches and these characters show up in my short stories as well, the archetype of a bruxa is in both cultures. An herb woman or healer, a water reader, a well finder. Women, magic and water are the holy trinity.

Q: Why do you think those who are between worlds are rarely heard?

A: People carry a cell phone like a pacifier, keeping some weird distraction going so they don’t have to even hear themselves thinking. You’re not going to hear the dead when you can’t even listen to yourself. Signs abound in life if you look, but easy answers win the popularity contest, you know good vs bad, heaven or hell, left or right. I read once that the deepest current at the bottom of the ocean is called a river and is nearly undetectable. The dead are like that, no? Deep somewhere, unseen, but pulling at the living world all the same, the way the moon moves the sea.

Q: Can you tell us other ways that being a Portuguese-American infuses your writing?

A: Everything I write: place, character, or influence of identity is a composite. I am never writing thinly-veiled memoir. My work is mosaic. All of me is somewhere inside the stories, but the power comes from knowing a place and a people well enough to re-imagine them. So I am always writing the real lives of imaginary people or the imagined lives of real people, but never the real life of real people.

Q: In your travels through Portugal, is there a places that calls home to you?

A: First, I would say, the mountains in Madeira. The forests near Santo da Serra, the levadas, the mist that hangs over the mountains is otherworldly. But for people, life there can be a very hard and isolated. I think the only fairytales in those mountains are the old kind where beauty and tragedy are sistered.

On the mainland, Nazaré. Artists from all over the world come to Nazaré and don’t want to leave, that is an old story. I love the sea air and beaches in September and October when there are no tourists to speak of, when you can really hear the wind, and birds and water in concert with one another. It still has the feeling of a real fishing village. It is a stunningly beautiful country. Unfortunately the average visitor often misses the amazing artists, musicians, puppet makers, woodcarvers, dressmakers, and intellectuals that make up the artistic capital of Portugal. Maybe that is her greatest wealth.

Here is an excerpt from Primitivity, a piece called “Lard”

You can train a man on most things he needs to know using regular table food, my Auntie Gin says. See this? She pinches an inch of skin above her hip. That’s lard that got that there. . .

Pretty is overrated. Pretty never held nobody in place but the poor gal trying to maintain it. Lard has its risks, and has been known, in equal shares, to make a winning pie crust and cause heart trouble. You do with that information as you please. She takes a deep, crackling drag on a rolled cigarette.

See this?

She holds the back of her hand under the table lamp and pulls back the skin, that’s what I used to look like, what you still have. Don’t waste it. The hands and the neck give you away every time. God bless Jessica Lange, if it don’t. There are fixes for all your troubles if you know where to start.

Q: Is the character Auntie Gin based on a real person?

A: Auntie Gin is a composite for sure. I grew up around a lot of straight-talking women. She is born from those voices. Aunts, Great Aunts, Grandmother’s and their friends who dispersed wisdom while going about their business, weeding gardens, killing chickens, dealing with every possible iteration of patriarchy as they tried to thrive.

I remember women often disappointed by men, damaged and let down. Women having to figure out how to make a life around situations that men created. So I guess these are fighting back stories, re-claiming. A fellow CantoMundista, Denice Frohman, wrote a poem #SheInspiresMe where she says, “I heard a woman becomes herself/ the first time she speaks/without permission.” That is the essence of my Auntie Gin character, she’s got permission by the ear and she’s shaking it hard as a way to pass down that wisdom.

One of your stories, in particular, “Fire Bringer” a child wants a story (for a school project) about how her grandparents met and fell in love, but instead she gets something else entirely. Here’s an excerpt:

So I asked her, Helen Riddle of Crain Hill, Tennessee, “How did you meet Granddaddy?”

She said, “There’s two kinds of men in the world. The ones that make you warm and the ones that keep you warm. If you plan on getting married and staying that way, sugar, you’d do well to ponder the distinction.”

Thinking she did not understand, I repeated the question. “But how’d you meet Granddaddy?”

“Corn,” she said. “And a side of bacon.”I laughed. She didn’t.

“This was the Depression,” she said. “The corn he brought was to burn. We’d had no proper wood for a month.”

She paused, rested her face in her palm for a second.

“Corn burns hot. My own father, your great-granddaddy, was a college man. The one thing he never learned though was surviving hard times. Contrary to popular belief, books don’t burn well. King Lear won’t keep you warm in January when the chill off the river creeps in every crack and cranny. Your muscles ache from holding on to yourself so tight. Our good parlor furniture turned to ash quicker than kindling wood. Then here your granddaddy came up the road. That stride. Sack of gold pellets slung over his shoulder.”

“But was he cute,” I interrupted.

“Cute? Lord no,” she replied. “He was a man. Dark and stout as a bull.”

“But what did he look like?” I asked with the intensity of having never seen the man I had loved my whole twelve years on earth.

“Like he was built of plenty and God’s own bounty. He walked like a man with a place to be. He walked like that his whole life.”

“But what does that look like?” I asked.

“Like heat and food,” she said

Q: Your stories are filled with families and lessons learned. Can you tell me more about your history?

A: My grandparents had what country people called a hunger marriage, where people from different socio-economic class and ethnicity came into the same circle due to the circumstances of the Depression.

My Grandmother Sayre went to college and my Grandfather didn’t go past the sixth grade because he worked. But her people lost everything, and I remember her telling me that he brought a sack of corn to her father on their first date, and how hot that corn burned. He may not have been conventionally educated, but he was a man to be reckoned with. When he put his word or his shoulder to a task, it got done.

My grandmother knew what it meant to watch the world come apart, and I suppose Grandfather looked like the man to put it back together with. I don’t know if that is romantic, but it is an abiding kind of love. In times more flush they might never have met, but I hope this story is a way of honoring the fact that they did.

Q: The stories in Primitivity are vivid, little chestnuts of dialogue and you’ve created a whole world of characters. Were you thinking of the collection as, potentially? A novel?

A: I am putting the finishing touches on the full-length manuscript which contains a novella and inter-linked short stories. I think the stories stand alone and build a world. I consider them as performance pieces too.

Q: Pike County, where the stories take place—is that real?

A: The Pike County in my book is a composite also of several places. Pike County Illinois is next to the county I grew up in, and there is also a Pike County, Kentucky and Ohio. I liked the idea of mashing these places together connected by river and mountain and dialogue. Language is type of landscape in book, so I pushed the latitudes and longitudes to suit me.

Q: This could almost be called How To Survive (handbook) sort of a rural version of Emily Post. What to do and not to do. Like, Rough Rules for Living. What lesson hits home for you?

A: There’s a story, “Pike County Feminism,” where Auntie Gin discusses “be careful out your mama’s mouth just means take care of yourself better than I did.” I think that is a lesson many of us learn at some point. Some of us earlier than others, and some of us need the rest of our life to process it. That is not parent blaming, simply that when you are poor and female, a person of color, trans, queer, when you are an immigrant or outside societies favored few in any multitude of ways, you find your choices narrowed, you find help does not come to your calling, and that is life’s opportunity to eat you right down to the bone.

I love how your stories begin WHAM. Like this one:

When Trevor’s dad bought an event track

Or

A science man studies the world to say why, say how it got made. A Pike County man ciphers the world for what it is, and how to survive it.

Starting in the middle immediately draws readers in. Was that intentional?

A: Thank you and it was. I guess “en media res” or starting in the middle, is one of those old fiction writers’ maxims that stuck. I like to read a story where much is left to the imagination.

What you can imagine is always bigger, scarier and grander than what you could solidify. Margaret Atwood does it, and Toni Morrison does it, and I love when writing has the reader looking between the lines, saying, “Wait, what?!” If I have gotten a bit of that, then I am happy.

————————–

Millicent Borges Accardi is the author of three books, most recent, Only More So (Salmon Poetry). She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), Fulbright, CantoMundo, California Arts Council, Fundação Luso-Americana (FLAD), and Barbara Deming. She organizes Kale Soup for the Soul: Portuguese-American writers reading work about family, food and culture. Follow her @TopangaHippie (on Twitter).

Millicent Borges Accardi is a pro bono contributor for the Portuguese American Journal. Because you value her work please donate to paypal.me/Millicent500